Why Your Diesel Engine’s Cylinder Head is the Unsung Hero of Performance

A diesel engine cylinder head is the critical metal component that sits atop your engine block, sealing the cylinders and forming the combustion chamber where power is generated. Here’s what you need to know:

Key Functions:

- Seals the combustion chamber – Creates an airtight seal over the cylinder bore

- Houses critical components – Contains valves, fuel injectors, and valve train components

- Manages airflow – Controls intake of fresh air and exhaust of spent gases

- Dissipates heat – Channels coolant to prevent overheating

- Shapes combustion – Determines compression ratio and fuel-air mixing efficiency

Think of your cylinder head as the control center for combustion. While the engine block provides the foundation, the cylinder head orchestrates everything that happens inside the combustion chamber. It’s where fresh air enters, where fuel is injected under extreme pressure, and where exhaust gases exit after combustion.

For marine and industrial diesel engines, the cylinder head faces particularly harsh conditions. Saltwater corrosion, thermal cycling from variable loads, and the extended run times common in commercial applications all take their toll. A cylinder head on a fishing vessel operating 12-hour days or an industrial generator running continuously faces far more stress than typical automotive applications.

The design of your cylinder head directly impacts engine performance, fuel efficiency, and reliability. Whether you’re managing a fleet of vessels in the Caribbean or maintaining an industrial power generation system, understanding how this component works helps us spot problems early and avoid catastrophic failures.

What is a Cylinder Head and What Does It Do?

Think of the diesel engine cylinder head as the lid on a pressure cooker—except this lid needs to contain thousands of controlled explosions every minute while managing extreme temperatures that could melt steel. It’s the critical component that sits atop your engine block, sealing each cylinder and creating the space where fuel transforms into power.

But calling it just a “lid” doesn’t do it justice. Your cylinder head is actually the command center for everything that happens during combustion. It’s where air flows in, where fuel gets injected under tremendous pressure, and where exhaust gases make their exit. Without a properly functioning cylinder head, your marine vessel or industrial equipment isn’t going anywhere.

Sealing the cylinder is the head’s most fundamental job. It creates an airtight and liquid-tight seal with the engine block, trapping the intense pressures generated during combustion. This seal is maintained by the head gasket—a specialized component we’ll talk more about shortly. Lose that seal, and you lose compression, power, and eventually, your entire engine.

The cylinder head also forms the combustion chamber itself. The underside of the head, combined with the piston crown and cylinder walls, defines the exact shape and volume where combustion occurs. This isn’t just about creating a space—the precise shape influences how air and fuel mix, which directly impacts your engine’s efficiency and power output.

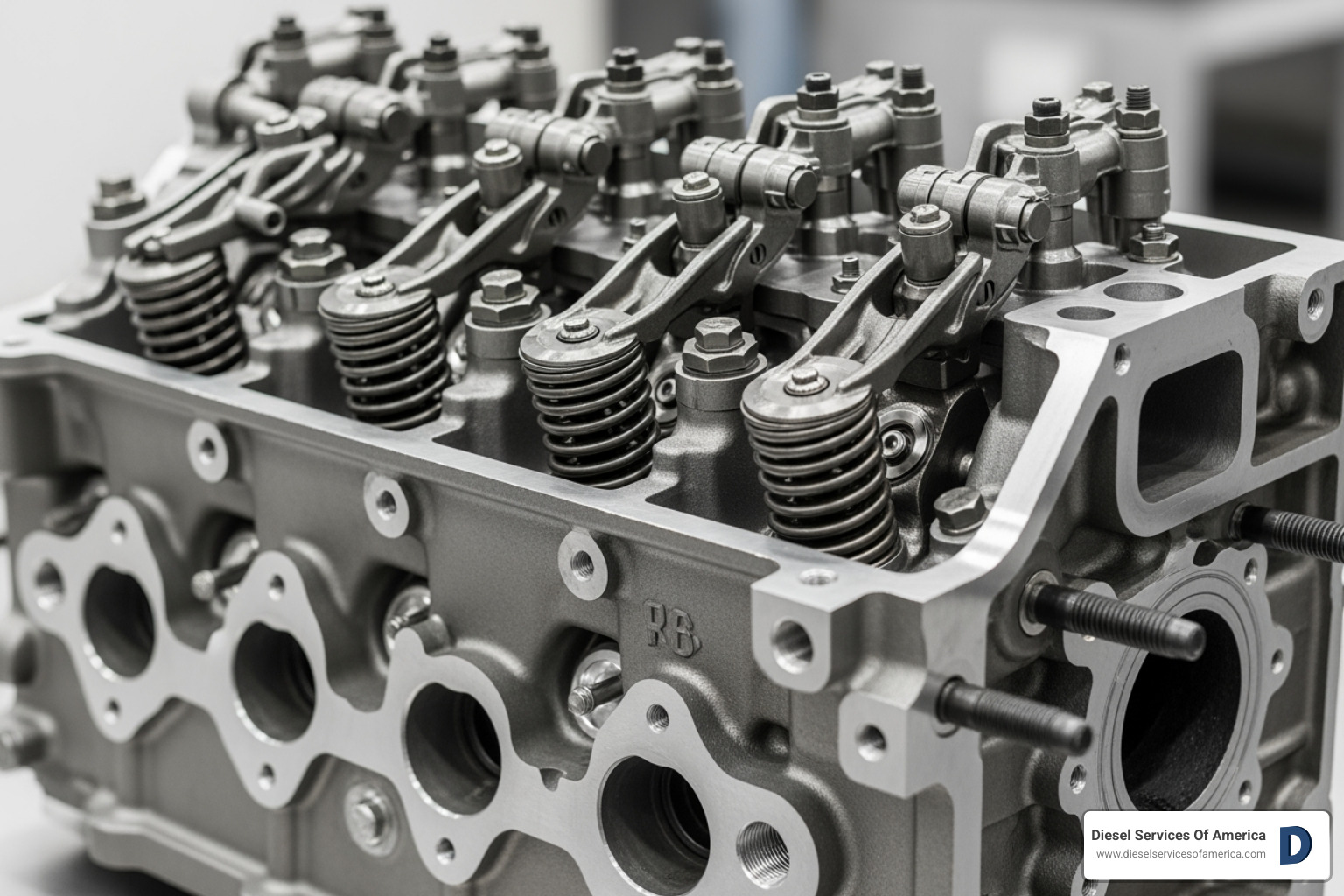

Inside the cylinder head, you’ll find a neighborhood of critical components working together. Intake valves let fresh air rush in. Exhaust valves push spent gases out. Valve seats provide a sealing surface for those valves. Valve springs keep everything moving in perfect rhythm. Fuel injectors deliver precisely metered diesel fuel at the exact right moment. In some designs, you’ll also find rocker arms or even camshafts living inside the head. It’s a busy place up there. For more technical background on cylinder head design, you can explore additional resources about cylinder heads.

Managing airflow is where engineering meets art. The intake ports in your cylinder head are carefully shaped to deliver fresh air efficiently into the combustion chamber. The exhaust ports are designed to let spent gases escape with minimal restriction. The design of these passages directly affects how well your engine “breathes,” which determines everything from fuel economy to maximum power output.

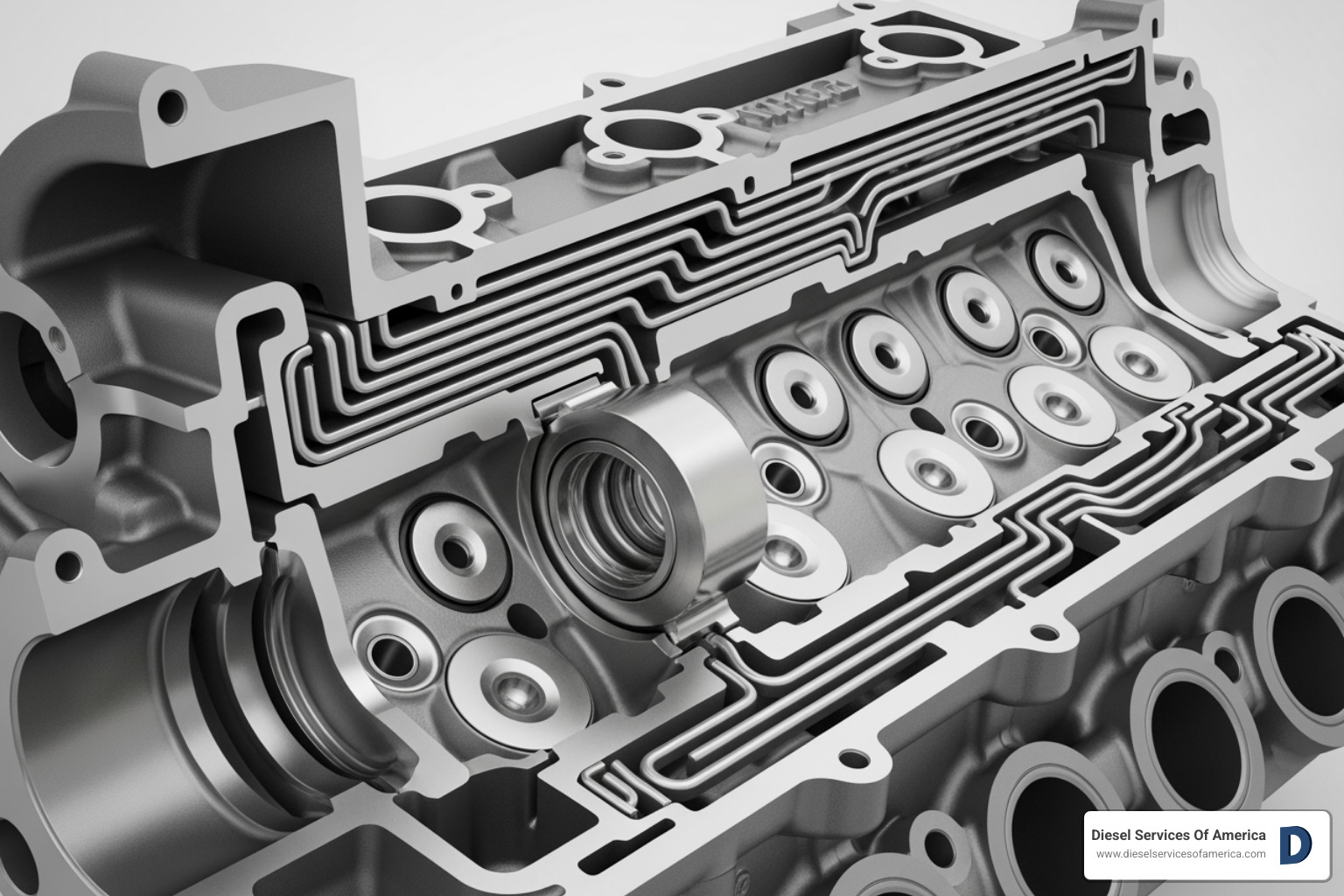

Heat management is another critical function. Diesel engines generate tremendous heat, and the cylinder head sits right at ground zero. That’s why it’s crisscrossed with intricate coolant passages—sometimes called coolant jackets—that allow engine coolant to circulate and absorb heat. This prevents dangerous hot spots that could warp or crack the metal. Without proper coolant flow through these passages, your cylinder head would quickly overheat and fail.

Finally, oil passages run through the cylinder head to lubricate all those moving parts we mentioned—valves, springs, camshafts, and rocker arms. These passages ensure a constant supply of oil reaches every component that needs it, reducing friction and preventing premature wear.

For marine diesel engines operating in saltwater environments or industrial engines running continuous duty cycles, the cylinder head faces particularly harsh conditions. That’s why understanding how it works is crucial for anyone managing vessels in Fort Lauderdale, throughout Southeast Florida, or across the Caribbean.

The Cylinder Head’s Role in Combustion

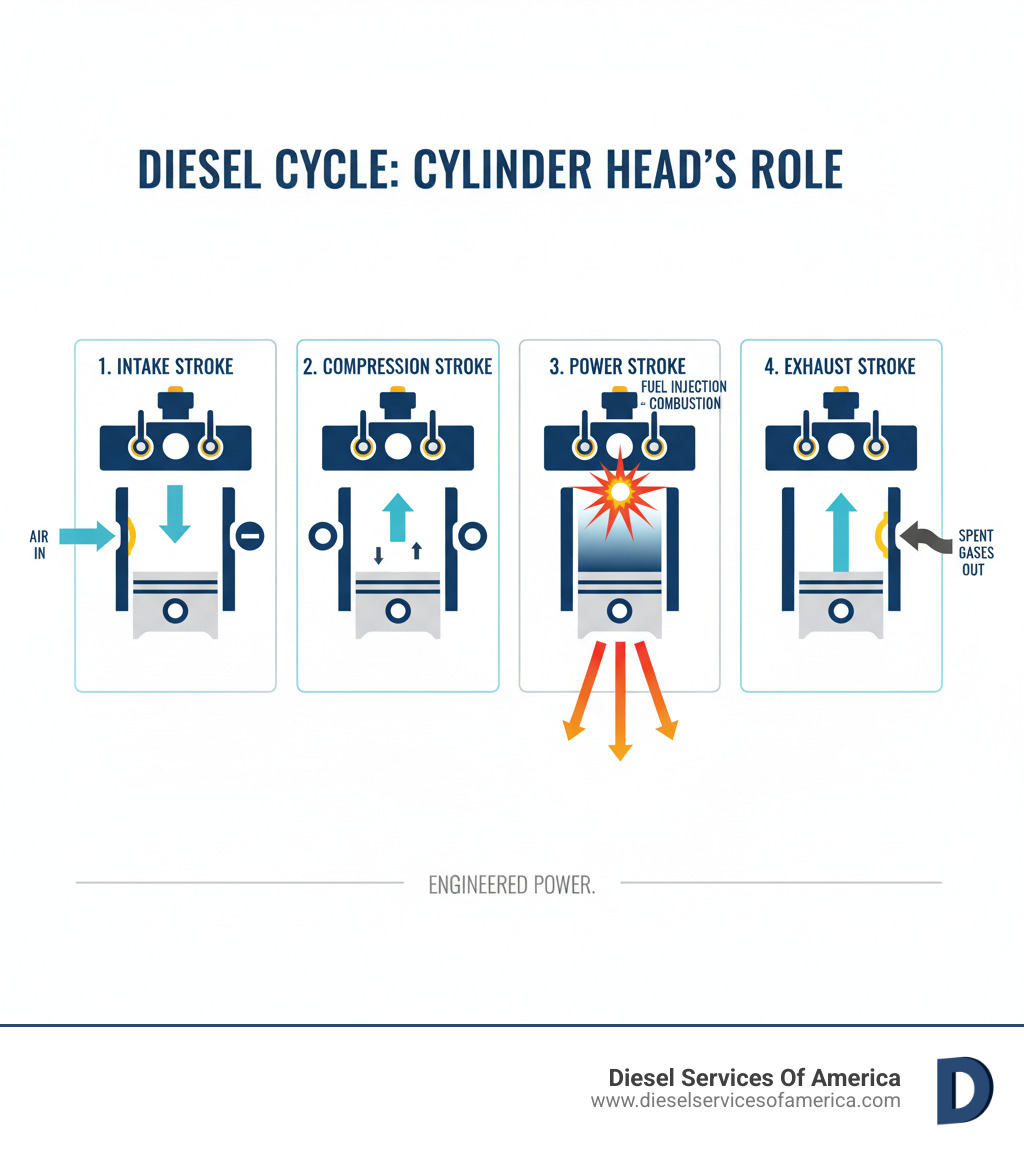

Here’s where things get interesting. Unlike gasoline engines that need a spark plug to ignite fuel, diesel engines rely on pure compression. The cylinder head plays a starring role in making this happen.

When the piston rises during the compression stroke, it squeezes air into the small space formed by the cylinder head’s combustion face. This compression heats the air to temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit—hot enough to spontaneously ignite diesel fuel the moment it’s injected.

The compression ratio—determined by the cylinder head’s design and the piston’s travel—is critical to this process. Marine and industrial diesel engines typically run much higher compression ratios than gasoline engines, which is what makes compression ignition possible in the first place.

Fuel atomization is another key function. The cylinder head houses the fuel injectors in precisely engineered bores, positioning them at exactly the right angle and location. Modern diesel injectors spray fuel at pressures exceeding 30,000 PSI, creating a fine mist that mixes thoroughly with the super-heated air. The better the atomization, the more complete and efficient the combustion.

Many cylinder heads feature intake ports shaped to create swirl and tumble patterns in the incoming air. This controlled turbulence helps mix the air and fuel more thoroughly, leading to cleaner, more efficient combustion. Think of it as stirring the pot to ensure everything cooks evenly—except this pot is experiencing temperatures that would vaporize most cooking vessels.

The result of all this careful engineering? Maximum combustion efficiency, which means more power from less fuel and cleaner exhaust emissions.

Managing Extreme Heat and Pressure

Let’s be honest—the environment inside a running diesel engine is absolutely brutal. We’re talking about thousands of controlled explosions per minute, temperatures hot enough to glow, and pressures that would crush most materials. Your diesel engine cylinder head sits right in the middle of this chaos and somehow keeps everything running smoothly.

Material selection makes all the difference here. Cast iron construction has been the workhorse material for marine and industrial diesel heads for decades, and with good reason. Cast iron offers exceptional durability and excellent heat resistance. It can handle the sustained thermal stress of continuous operation without warping or cracking. If you’re running a generator 24/7 or operating a commercial vessel with long duty cycles, cast iron’s robust nature is exactly what you need.

Aluminum alloys offer some advantages—they’re lighter and transfer heat faster—but they’re more common in automotive applications. Some modern marine and industrial diesels do use aluminum heads, often with reinforced areas around critical zones, but cast iron remains the gold standard for heavy-duty applications.

The coolant flow system within the cylinder head is absolutely vital. These intricate passages route coolant around the combustion chambers, valve seats, and injector bores—basically anywhere heat concentrates. The coolant absorbs this heat and carries it away to your heat exchanger, preventing localized hot spots that could cause warping or cracking.

Then there’s the head gasket function—arguably one of the most critical sealing jobs in your entire engine. This multi-layered component sits between the cylinder head and engine block, maintaining a perfect seal under extreme conditions. It must prevent combustion gases from escaping, keep oil and coolant from mixing, and withstand constant thermal cycling as the engine heats up and cools down.

When a head gasket fails, the consequences cascade quickly. You might see coolant mixing with oil, loss of compression, overheating, or white smoke from the exhaust. In marine environments where engines run for extended periods, or in industrial applications with continuous duty cycles, the head gasket faces particularly demanding conditions. That’s why proper installation torque and regular maintenance are so critical for vessels operating out of Fort Lauderdale and throughout the Caribbean.

Anatomy of a Diesel Engine Cylinder Head

If you’ve ever wondered what makes a diesel engine cylinder head tick, let’s pull back the curtain and explore the intricate world inside this precision-engineered component. Every channel, bore, and passage has been carefully designed to perform a specific job—and when you’re dealing with marine and industrial diesels in Fort Lauderdale or across the Caribbean, understanding this anatomy helps you appreciate why proper maintenance is so critical.

The intake ports are where the journey begins for each breath of fresh air. These aren’t just simple holes drilled into the head—they’re carefully sculpted channels that guide filtered air from the intake manifold into the combustion chamber. Their shape matters tremendously, creating that swirling, tumbling motion we mentioned earlier that helps mix air and fuel perfectly.

Once combustion happens and the fuel has done its job, the exhaust ports take over. These passages channel those hot, spent gases away from the cylinder and into the exhaust manifold. Think of them as the exit doors after the party—they need to be efficient enough to clear everything out quickly so the next cycle can begin.

Right in the heart of the action, you’ll find the fuel injector bores. These precision-machined openings house the fuel injectors, positioning them so the injector tip extends directly into the combustion chamber. This allows them to spray atomized diesel fuel right into that superheated compressed air at exactly the right moment.

The valve guides are the unsung heroes that keep everything moving smoothly. These cylindrical inserts provide a precise pathway for the valve stems, ensuring they glide up and down without wobbling or binding. After thousands of hours of operation on a fishing vessel or industrial generator, worn valve guides can cause all sorts of headaches.

Surrounding all these high-temperature areas, you’ll find the coolant jackets—an intricate network of internal passages that form a cooling system within the cylinder head itself. Engine coolant flows through these channels, wrapping around valve seats and injector sleeves like a protective blanket, carrying away the intense heat before it can cause damage.

Valves, Seats, and Springs

The valves are the gatekeepers of combustion, opening and closing thousands of times per minute to control the flow of gases. The intake valves swing open during the intake stroke, welcoming fresh air into the cylinder. Then the exhaust valves take their turn, opening to release the spent gases after combustion. Both types are forged from high-strength, heat-resistant alloys because they face some of the harshest conditions in the entire engine.

But a valve is only as good as its seal. The valve seat—either machined directly into the cylinder head or pressed in as a separate hardened insert—is where the valve creates an airtight seal when closed. This contact point must be perfect. Even the tiniest gap here means lost compression and hot combustion gases escaping, which can quickly erode both the valve and the head material. In the marine engines we service, valve seat damage is one of the most common issues we encounter in high-hour applications.

The valve springs and retainers work behind the scenes to slam those valves shut quickly and keep them sealed tight against their seats. These springs must be strong enough to overcome not just the valvetrain forces but also the pressure inside the cylinder trying to blow the valves open at the wrong time.

Depending on the engine design, rocker arms (in overhead valve engines) or cam lobes acting directly on the valves (in overhead cam engines) transmit the motion from the camshaft to open each valve at precisely the right moment. It’s a mechanical ballet that happens continuously while your engine runs.

The key valvetrain components you’ll find in or interacting with the cylinder head include intake valves, exhaust valves, valve seats, valve guides, valve springs, valve spring retainers, rocker arms (in OHV designs), camshafts (in OHC designs), and lifters or tappets.

Gas Intake and Exhaust Methods

Here’s where diesel engines get interesting. Unlike their gasoline cousins, diesel engines have multiple ways to get fresh air in and exhaust gases out. The method depends largely on whether you’re dealing with a two-stroke or four-stroke design.

Most modern four-stroke diesel engines—the type you’ll commonly find in marine and industrial applications throughout Southeast Florida—use traditional poppet valves. These are the intake and exhaust valves housed in the cylinder head that we just discussed. The valvetrain mechanically opens and closes them at precise intervals, giving excellent control over gas flow and combustion efficiency.

But some two-stroke diesel engines, particularly the large industrial and marine powerhouses, use a different approach with ports. Instead of valves, these engines have slots cut into the cylinder walls. As the piston moves up and down, it uncovers and covers these ports. In a uniflow scavenging system, you might see intake ports in the cylinder liner working with exhaust valves in the cylinder head, creating a one-way flow of air that efficiently sweeps out the spent gases.

Many medium-sized diesels split the difference, using a combination of both methods—maybe intake ports with exhaust valves, or vice versa. The goal is always the same: get the maximum amount of fresh air into the cylinder and remove exhaust gases as efficiently as possible. Regardless of the specific method, the diesel engine cylinder head remains central to this gas exchange process.

Fuel and Coolant Passageways

Beyond the main combustion components, the cylinder head contains a hidden network of channels that keep everything running smoothly. These internal passageways are just as critical as the parts you can see.

The internal fuel galleries are precision-machined passages that carry high-pressure diesel fuel from the pump to each injector. Some cylinder heads integrate these fuel channels directly into the casting, creating a clean, protected path that minimizes external piping and potential leak points. It’s neat engineering that reduces the chances of fuel leaks—something you definitely don’t want on a marine vessel.

Just as important are the fuel return ports. Not all the fuel delivered to the injectors gets burned. The excess fuel, which also helps cool the injectors, needs a way back to the fuel tank. Many cylinder heads include integrated return passages that ensure a continuous flow of cool fuel to the injectors, preventing overheating in the fuel system.

The coolant circulation path within the cylinder head is remarkably sophisticated. Coolant doesn’t just flow randomly through those jackets we mentioned—it follows a carefully planned route that targets the hottest areas first. The passages concentrate flow around valve seats and injector bores, where temperatures peak during operation. This strategic cooling prevents localized hot spots that could lead to cracks or warping.

When coolant flows properly through these passages, heat gets distributed evenly and removed effectively, protecting the structural integrity of the entire cylinder head. It’s this kind of thermal management that allows marine and industrial diesels to run for thousands of hours without failure. For more detailed technical specifications on these intricate internal systems, you might find technical details in diesel engine books.

Design and Construction Variations

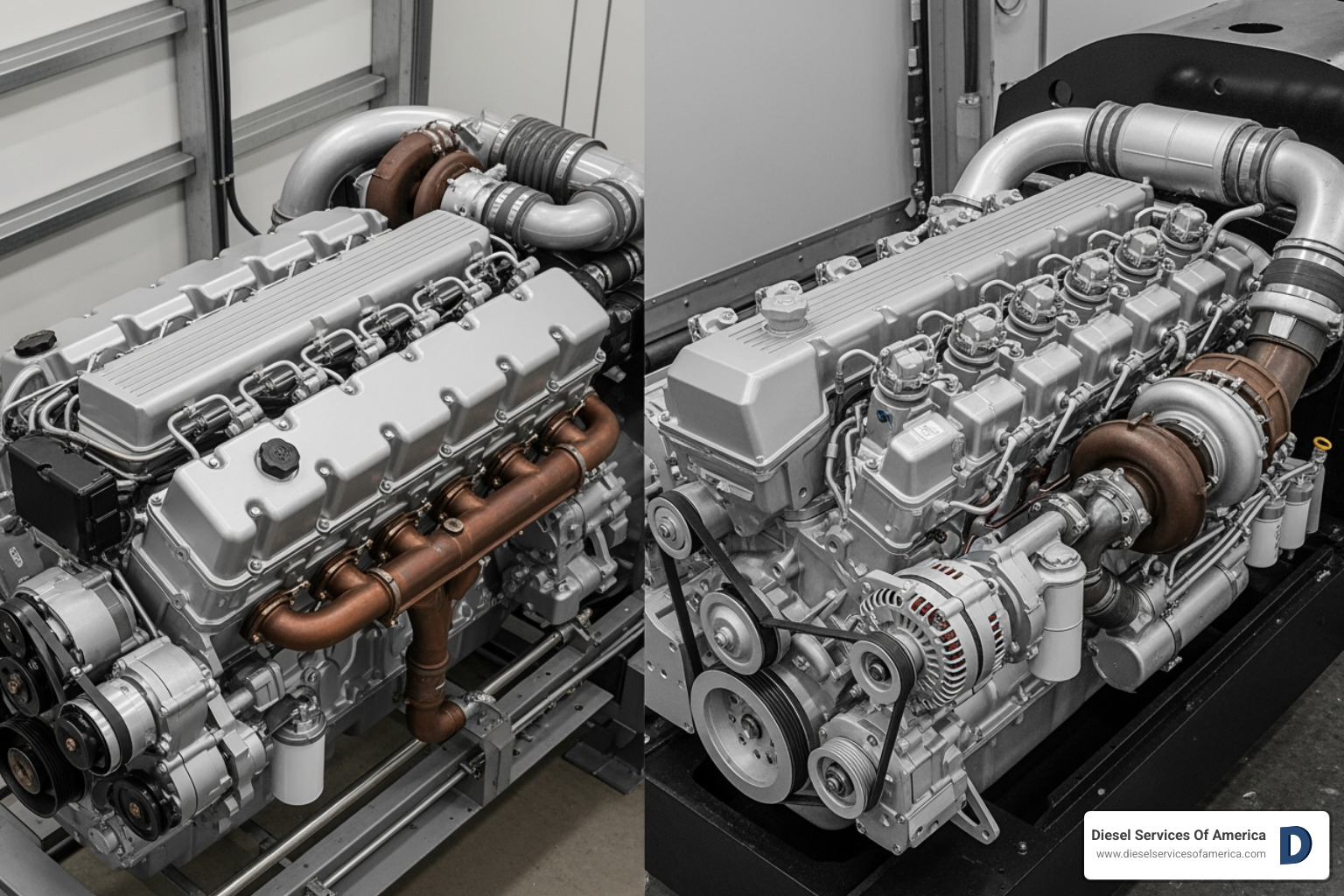

The world of marine and industrial diesel engines is incredibly diverse. From compact generators powering remote installations to massive propulsion systems driving cargo ships across the ocean, the diesel engine cylinder head adapts to meet each unique challenge. Understanding these design variations helps you make informed decisions when maintaining or replacing these critical components.

The basic architecture of cylinder heads varies significantly based on engine layout. Single-casting heads are typical in modern straight or inline engines, where one large, integrated piece covers all cylinders arranged in a row. This design provides excellent structural rigidity and simplifies manufacturing, making it common in mid-sized marine and industrial applications.

Engines with different configurations require different approaches. V-layout or flat-layout engines typically use two separate cylinder heads, one for each bank of cylinders. This allows engineers to create more compact engine designs while still accommodating multiple cylinders—particularly useful when space is at a premium in engine rooms.

But here’s where larger marine and industrial engines get interesting: many use individual cylinder heads, with one separate head for each cylinder. This might seem like extra complexity, but for heavy-duty applications running in the Caribbean and beyond, it’s actually brilliant engineering that saves time and money when problems arise.

How a Diesel Engine Cylinder Head is Manufactured

Creating a diesel engine cylinder head is part art, part science. The process combines time-tested foundry techniques with cutting-edge precision machining to produce components that can withstand years of demanding service.

Everything starts with the casting process. Molten metal—either cast iron for maximum durability or aluminum alloy for better heat transfer—gets poured into intricate sand or permanent molds. These molds define the basic shape, including those complex internal passages for coolant and oil that we discussed earlier. The choice between cast iron and aluminum depends on the engine’s specific needs: cast iron dominates in heavy-duty marine and industrial engines where strength and longevity matter most.

Once the raw casting cools and is removed from the mold, the real precision work begins. CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machining takes over, milling surfaces to tolerances measured in thousandths of an inch. These sophisticated machines drill bolt holes, shape intake and exhaust ports, and machine valve seats to exact specifications. High-performance heads often receive extra attention here, with advanced port shaping to optimize airflow.

Many cylinder heads then go through heat treatment processes to improve their metallurgical properties. This controlled heating and cooling improves hardness, strength, and resistance to the thermal fatigue that comes from thousands of heating and cooling cycles during normal operation.

Finally, quality control inspections ensure every head meets specifications. Technicians perform visual checks, precise dimensional measurements, and sometimes even X-ray or ultrasonic testing to detect any internal flaws that could compromise performance or longevity.

Individual vs. Multi-Cylinder Heads for Large Engines

When you’re dealing with large marine diesel engines—the kind powering commercial fishing vessels, cargo ships, or industrial generators—the choice between individual and multi-cylinder head designs has real-world consequences for your operation.

Individual cylinder heads offer a compelling advantage: reduced repair costs. Imagine you’re running a 12-cylinder marine engine and a valve seat fails in cylinder number seven. With a single multi-cylinder head covering all twelve cylinders, you’d need to remove and repair or replace that massive, heavy casting. With individual heads, you simply address the one affected cylinder. The difference in labor hours and parts costs can be substantial.

Easier maintenance is another benefit we see regularly in our Fort Lauderdale facility. Individual heads are lighter, more manageable, and can often be serviced without removing adjacent components. This means faster turnaround times and less disruption to your operations—critical when you’re losing revenue every day a vessel sits at the dock.

The modularity of individual head designs also provides flexibility in engine design and configuration. Manufacturers can use the same basic cylinder head across different engine sizes, simply adding or removing cylinders as needed. This standardization can improve parts availability and reduce inventory costs.

| Feature | Individual Cylinder Heads | Multi-Cylinder Heads |

|---|---|---|

| Repair Cost | Lower – only affected cylinder needs attention | Higher – entire head must be removed |

| Weight | Lighter and easier to handle | Heavy, often requires lifting equipment |

| Maintenance Access | Better – can work on one cylinder at a time | More difficult – adjacent cylinders may interfere |

| Downtime | Reduced – faster repairs possible | Extended – more labor intensive |

| Common Applications | Large marine and industrial engines | Smaller to mid-sized engines |

This design philosophy is particularly common in large marine and industrial applications where reliability and maintainability directly impact profitability.

Valvetrain Configurations: OHV vs. OHC

The way valves are actuated in a diesel engine cylinder head significantly affects engine performance, maintenance requirements, and overall design. The two primary configurations you’ll encounter are OHV and OHC designs, each with distinct characteristics.

Overhead Valve (OHV) designs, sometimes called pushrod engines, keep the camshaft in the engine block. Long pushrods transfer motion from the camshaft up to rocker arms mounted on top of the cylinder head, which then push the valves open. This traditional design is compact, robust, and easier to service—qualities that make it popular in many marine and industrial diesel applications. The simplicity means fewer things can go wrong during extended operation at sea or in remote industrial sites.

Overhead Camshaft (OHC) designs mount the camshaft directly in the cylinder head, eliminating pushrods entirely. This can come in two forms: Single Overhead Cam (SOHC), where one camshaft operates both intake and exhaust valves, or Double Overhead Cam (DOHC), where separate camshafts handle intake and exhaust valves independently.

The OHC approach reduces valvetrain inertia—there are fewer moving parts between the camshaft and the valves. This allows higher engine speeds and more precise valve timing, which can improve efficiency and power output. However, OHC designs are more complex and can be more challenging to service, especially in the confined spaces of an engine room.

For the heavy-duty marine and industrial engines we service throughout Southeast Florida and the Caribbean, OHV designs remain popular because they prioritize reliability and serviceability over ultimate performance. When your engine needs to run continuously for thousands of hours between overhauls, simplicity becomes a valuable feature.